漢字到底是什麼 ?What exactly is a Chinese character then?

It may be obvious to some, less to others, but the Chinese writing system is not based on an alphabet.

An alphabet consists of a small number of letters. Letters represent sounds.

They spell out how words should be pronounced. Letters don’t have any meaning by themselves.

They spell out how words should be pronounced. Letters don’t have any meaning by themselves.

A Chinese character on the other hand is a more complex unit.

It contains an indication of pronunciation as well as an indication ofmeaning.

There are more than 100,000 different Chinese characters.

It is actually impossible to count them precisely! There are infinite variants.

The number of useful characters, for a literate person however, is “only” between 3,000 and 6,000.

That is still a huge number compared to the 26 letters of our alphabet.

But you can’t compare apples and oranges!

It contains an indication of pronunciation as well as an indication ofmeaning.

There are more than 100,000 different Chinese characters.

It is actually impossible to count them precisely! There are infinite variants.

The number of useful characters, for a literate person however, is “only” between 3,000 and 6,000.

That is still a huge number compared to the 26 letters of our alphabet.

But you can’t compare apples and oranges!

What exactly is a Chinese character then?

Here is one way to look at it: take the English word “unexpected” for example.

Let’s split it into smaller units of meaning: [UN]-[EXPECT]-[ED].

Well, Chinese characters are like those 3 parts.

In Chinese, UN would be a character, EXPECT would be another, and EDwould be yet another.

The word “unexpected” would then be a 3-character word.

Let’s split it into smaller units of meaning: [UN]-[EXPECT]-[ED].

Well, Chinese characters are like those 3 parts.

In Chinese, UN would be a character, EXPECT would be another, and EDwould be yet another.

The word “unexpected” would then be a 3-character word.

Let’s take an actual Chinese word as example and see how this works:

昨天 => yesterday

We have 2 characters here: 昨 + 天.

Let’s imagine we can split it in English the same way: [YESTER] + [DAY].

As in English, the second character 天, means day.

And as in English, the first one is not a word if taken alone.

But it is sufficiently unique to give the whole word its meaning.

Let’s imagine we can split it in English the same way: [YESTER] + [DAY].

As in English, the second character 天, means day.

And as in English, the first one is not a word if taken alone.

But it is sufficiently unique to give the whole word its meaning.

Now, let’s invent a word in English and Chinese at the same time:

昨月 => yestermonth

You can guess what I mean with this word, and a Chinese person would probably guess what I mean too, even if those words don’t actually exist.

This is to show that yester and 昨 carry a meaning of their own, even if they are not words.

This is to show that yester and 昨 carry a meaning of their own, even if they are not words.

I hope this gives you a sense of what Chinese characters are and how they differ from words and letters.

Now there are a few differences between Chinese characters and Englishmorphemes (a morpheme is what those small word parts like yester, day,un, expect, ed would be called by a linguist).

When I see 天, I see a small icon which represents a person extending his arms under the sky.

I see it this way, because that’s how it has been explained to me, and with a bit of imagination, it makes sense.

The first meaning of 天 is “sky” and by extension “day”.

So, Chinese characters are in a way, like small abstract pictures.

And that’s an important difference with English morphemes.

I see it this way, because that’s how it has been explained to me, and with a bit of imagination, it makes sense.

The first meaning of 天 is “sky” and by extension “day”.

So, Chinese characters are in a way, like small abstract pictures.

And that’s an important difference with English morphemes.

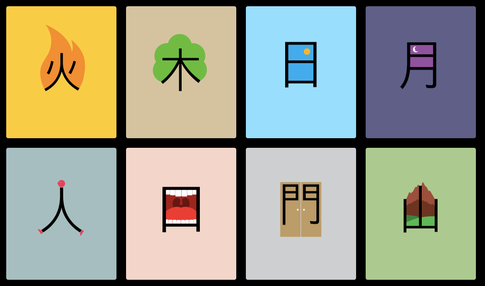

The picture bellow gives you an example of how characters can be seen as pictures. If you are curious about this, check the website where I found this picture: Chineasy.

Another difference is that English morphemes change to fit the words they contribute to.

The word “morpheme” is an indication of this phenomenon.

For example “day” becomes “dai” in the word “daily”.

There are many words in English for which it is hard to find the morphemes, because they blend together.

In addition, there are grammar rules like conjugation that further transform words so that their morphemes are not quite visible.

The word “morpheme” is an indication of this phenomenon.

For example “day” becomes “dai” in the word “daily”.

There are many words in English for which it is hard to find the morphemes, because they blend together.

In addition, there are grammar rules like conjugation that further transform words so that their morphemes are not quite visible.

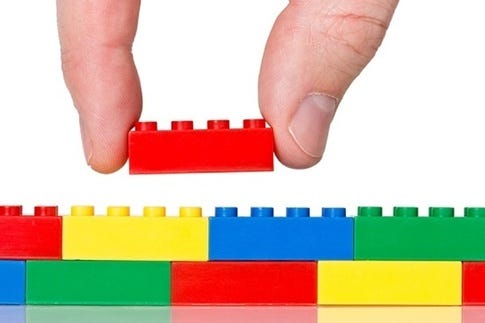

In Chinese, there is no conjugation, and the morphemes never blend in with their surrounding. Instead, words are made by composing characters like you would compose Lego bricks.

Here is a word I found interesting when I studied Chinese:

共产主义 => communism

It’s interesting because you can analyse it at multiple levels.

You can take it as a whole word, which means “communism”.

You can split it in 2: 共产+主义 (communist+ideology).

You can split it in 4: 共+产+主+义 (share+production+main+meaning).

The last part I interpret as something like: “the mainstream idea of shared production”, in other words, communism.

I find this quite interesting. The meaning of words seems more transparent than in English.

Like Lego bricks, you can de-construct words and re-assemble them more flexibly.

You can take it as a whole word, which means “communism”.

You can split it in 2: 共产+主义 (communist+ideology).

You can split it in 4: 共+产+主+义 (share+production+main+meaning).

The last part I interpret as something like: “the mainstream idea of shared production”, in other words, communism.

I find this quite interesting. The meaning of words seems more transparent than in English.

Like Lego bricks, you can de-construct words and re-assemble them more flexibly.

So far we have looked at Chinese characters from the outside.

Let’s take a look at what is inside a character.

Let’s take a look at what is inside a character.

Characters are drawn inside an invisible square that marks its borders.

So they all have roughly the same size, and they can really be assembled like bricks.

A Chinese text is like a grid of characters. Chinese kids, when they practice writing, use grid paper.

They are instructed to pay careful attention to the proportions and position of the characters inside the virtual square.

So they all have roughly the same size, and they can really be assembled like bricks.

A Chinese text is like a grid of characters. Chinese kids, when they practice writing, use grid paper.

They are instructed to pay careful attention to the proportions and position of the characters inside the virtual square.

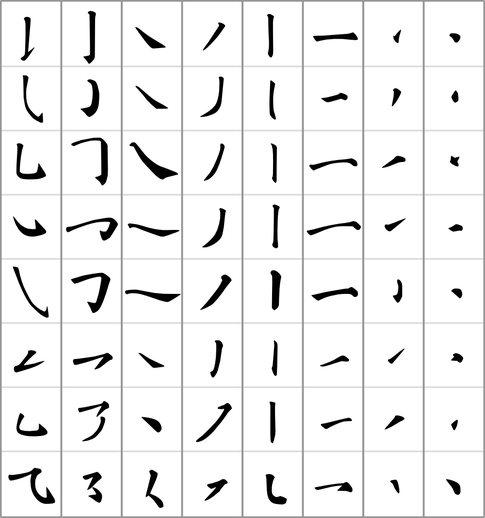

A character is not a random drawing. It is made of strokes. There are 6 basic strokes.

Some of them have several variants, and strokes can be combined to create more strokes.

But the basic idea is that most characters are made from a few, limited number of strokes.

Strokes have names. With only oral instructions, naming the strokes, I can describe any character.

In a way, strokes are closer to the concept of letters than characters are.

They are the smallest unit of Chinese writing.

Some of them have several variants, and strokes can be combined to create more strokes.

But the basic idea is that most characters are made from a few, limited number of strokes.

Strokes have names. With only oral instructions, naming the strokes, I can describe any character.

In a way, strokes are closer to the concept of letters than characters are.

They are the smallest unit of Chinese writing.

Stroke order is important. Kids learn which stroke goes before which at school.

It is important because of how muscle memory works.

Our brain is able to automatically remember a complex sequence of movement.

If strokes were written in a random order, they would be much harder to remember.

Because the rules and patterns of stroke ordering are few in number, characters that look very complex at first, are in fact a rather simple familiar sequence of strokes.

It is important because of how muscle memory works.

Our brain is able to automatically remember a complex sequence of movement.

If strokes were written in a random order, they would be much harder to remember.

Because the rules and patterns of stroke ordering are few in number, characters that look very complex at first, are in fact a rather simple familiar sequence of strokes.

The patterns of stroke order is analogue to the pattern in letter order in English. Let’s invent two words at random: “fdsqkjg” and “stargomist”.

Which one seems more plausible? Can you see the reason why?

Yes, there are patterns in English that dictate which sequence of letters are plausible and which are not. The same goes for strokes in a Chinese character.

Which one seems more plausible? Can you see the reason why?

Yes, there are patterns in English that dictate which sequence of letters are plausible and which are not. The same goes for strokes in a Chinese character.

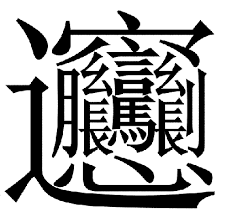

Complex characters can be broken down at a higher level than strokes.

The character above: 国, can be broken down into 2 components: 囗 and 玉

The character above: 国, can be broken down into 2 components: 囗 and 玉

The vast majority of characters in Chinese are compound characters.

They can be broken down into 2 or more components, and these componentsin turn can be broken down.

They can be broken down into 2 or more components, and these componentsin turn can be broken down.

There are several ways in which characters can be broken down intocomponents, I’m not going to give you all the details here, for the sake of conciseness.

The important thing to remember is that a component in a character can take on one of those functions:

The important thing to remember is that a component in a character can take on one of those functions:

- Meaning component (adds to the character’s meaning)

- Sound component (gives an indication of pronunciation for the character)

- Empty component (is only there to make the character distinct from other characters)

A great many Chinese characters have 2 components, one to indicate thepronunciation, and one to indicate the meaning.

Even the most complex Chinese character, with its 56 strokes, can be broken down into familiar components.

Components and strokes are the basis on which all Chinese characters are built.

Once you master these building blocks, you can analyse and learn any character efficiently.

Once you master these building blocks, you can analyse and learn any character efficiently.

Now that we have a better idea of what a Chinese character is, and how it differs from a letter in an alphabet, let’s figure out how hard it is to learn them as a Chinese kid.

Let’s break this down into several questions:

Let’s break this down into several questions:

How long does it take a Chinese kid to…

- Learn a few characters?

They learn to recognize a few simple characters before going to school.

Simple characters are like small pictures, so Chinese kids can actually start reading much earlier than kids who need to use an alphabet.

Simple characters are like small pictures, so Chinese kids can actually start reading much earlier than kids who need to use an alphabet.

- Learn the strokes and their ordering rules?

Around age 6–7, by the end of first grade, they have a good understanding of the strokes and their rules.

- Learn the most frequently used character components?

By age 11–12, at the end of primary school, they master the breaking down of characters into components, and they know enough components to learn any character.

- Learn enough characters to read any book or newspaper without a dictionary?

At some point, learning new characters becomes like learning new words.

You learn most of them just by encountering them enough times to grasp their meaning from context.

Chinese adults are intimately familiar with several thousands of characters.

For these, they see the meaning and pronunciation instantly, without any analysis.

For thousands of more characters, they can analyse and guess from context their meaning and pronunciation.

If they want to be sure, they sometimes have to resort to using a dictionary. Just like us!

You learn most of them just by encountering them enough times to grasp their meaning from context.

Chinese adults are intimately familiar with several thousands of characters.

For these, they see the meaning and pronunciation instantly, without any analysis.

For thousands of more characters, they can analyse and guess from context their meaning and pronunciation.

If they want to be sure, they sometimes have to resort to using a dictionary. Just like us!

written by Adrien Grandemange

Nov 27, 2015

0 意見:

張貼留言